We meet an icy seaward wind when we reach the top of the flood bank, and my eyes water as I scan the landscape through my binoculars.

It’s mid-afternoon, just after high tide, and in front of us is a breathtaking expanse of saltmarsh, mudflats and water. A flock of waders – we decide probably Dunlin – take flight in the distance, their pale bellies flashing white in the low January sun. A piping flock of Meadow Pipits and Skylarks flies over our heads to the fields behind us.

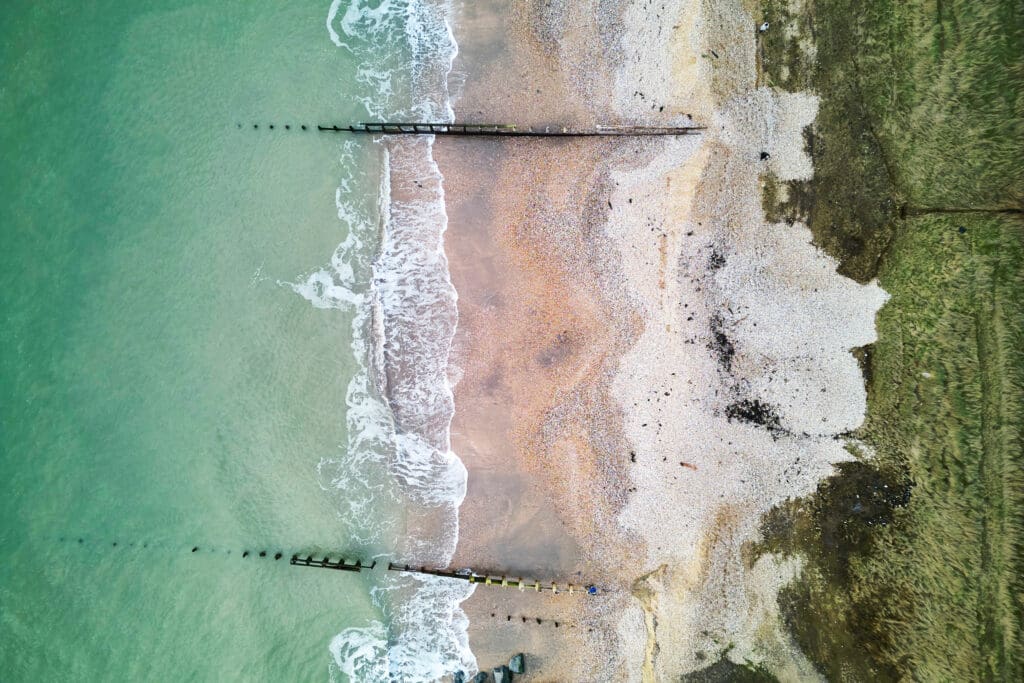

Here at RSPB Medmerry, on the coast just south of Chichester in West Sussex, one of Europe’s largest managed coastal realignment projects is 10 years old this year. The flood bank I’m standing on with Roy Newnham, the nature reserve’s Visitor Experience Manager, and Gail Richens, Conservation Ranger, might appear well-established, but the groundbreaking initiative was only completed in 2013. With its range of habitats, this youthful reserve – and its more mature neighbour RSPB Pagham Harbour – attract wetland, woodland and farmland bird species.

‘The combination of sun, ice and the spectacle of flocks of winter birds is hard to beat’

Climbing back down from the flood bank, we walk towards the shingle beach hoping for a sight of a rare winter migrant from continental Europe which has been reported here. A bird with a silhouette similar to a wagtail suddenly flits across the stones a few metres away. The smoky-grey body and wings, black face and orange-red tail confirm we’ve found the male Black Redstart. This is a first for me, a ‘lifer’ in the jargon. I’m elated and do a celebratory dance.

A century apart

Our visit began at RSPB Pagham Harbour Visitor Centre, and the aroma of coffee fills a warm room where visitors can defrost on a cold day, buy snacks and chat to staff. Nicole, one of today’s Welcome Team, tells me that she’s been volunteering here regularly for a year. “I love hearing which birds visitors have seen when they pop in to warm up,” she says.

This Visitor Centre serves both Pagham Harbour and Medmerry, and, while the nature reserves are within walking distance of each other, they have similar origins separated by a century. “Pagham was used as a harbour probably from the Saxon era until the 1870s and was then reclaimed for farming by damming the harbour mouth,” Roy tells me. The shingle sea wall was damaged by a storm in 1910, and from then on the tides flowed in and out. The 600-plus hectares of tidal mudflats, saltmarsh and wet grassland which formed were designated as a nature reserve in 1964. With evidence of Bronze Age settlers, remains of a Roman seaport and a Norman keep, the Pagham Harbour area has clearly been valued by humans for thousands of years. More recently, the Visitor Centre and a Discovery Zone were built on a reclaimed landfill site which was in operation until the 1970s.

Medmerry reserve is the new kid on the block, or rather the peninsula. Adam Taylor, RSPB Site Manager for Eastern Solent Reserves, tells me that before the coastal realignment flood bank was completed in 2013, the low-lying land around Medmerry was prone to flooding from high tides and storms putting nearly 350 homes at risk.

“The Environment Agency made the decision to work with partners such as the RSPB on a long-term nature-based solution rather than making endless costly repairs to the shingle bank,” Adam says.

“The 4.3-mile-long flood bank was constructed using material scraped from within the site itself and then a breach created in the shingle beach. Once construction was completed, the RSPB took on day-to-day management of the reserve. The project has been so successful that it’s now used as a case study in GCSE geography.”

‘It’s great to see Avocets doing well here despite the urban development around the two nature reserves’

Inundated with salt water twice daily since 2013, the 310-hectare area between Medmerry’s flood bank and shingle beach is still transforming into saltmarsh and mudflats, providing a safe nursery for young fish and habitats for feeding and resting waders and wildfowl. Environmentally friendly management of surrounding farmland has also led to increases in many species including Skylark, Yellowhammer, Linnet and Corn Bunting.

The coastal realignment excavation work was the perfect opportunity for archaeologists from University College London to explore Medmerry’s early history too. The Mesolithic flints and Neolithic pot shards found suggest that humans may have hunted and farmed in this area since 8,000BC. More recently in World War Two, the Medmerry area was used as a practice bombing range and ordinance is still found on the shingle beach. As well as minimising disturbance to wildlife, that’s another good reason for visitors to stick to the paths.

Plans are afoot to mark Medmerry’s 10-year anniversary and, once they’ve been confirmed, the reserve staff tell me they’ll be advertised widely.

Winter sights and sounds

After hearing about the fascinating history and ecology of the nature reserves, I walk with Roy and Gail along a path into Pagham Harbour, past the pond in the Discovery Zone which attracts Marsh Frogs, Grass Snakes and dragonflies in the summer.

A Tawny Owl box, complete with nest cam, is being installed on a tree beyond the pond by a work party volunteer to add to the bird and bee nest cams which are already linked to the screens in the Visitor Centre.

Beyond a wheelchair-accessible hide, we reach Ferry Channel, and find flocks of Wigeon whistling among patches of Sea Purslane; Redshank patrolling the mud; and Teal feeding. Over frosted Teasel heads, I spot a Marsh Harrier flapping leisurely across the saltmarsh. As an urban birdwatcher, I’m struck by how quiet it is here, other than the sound of birds, of course.

“This is my favourite time of year on the two reserves,” Gail tells me. “The combination of sun, ice and the spectacle of flocks of winter birds is hard to beat.” She points across the harbour to the inland sea wall on the opposite side of the reserve, “Looking out from North Wall over there on an incoming tide is my favourite place to be for great views of over-wintering waders and wildfowl.”

We scan the main harbour channel and can see large numbers of waders, but not the Dark-bellied Brent Geese which overwinter here from Siberia.

“I still can’t believe how lucky I am to now work in conservation after 22 years in the civil service,” Gail says, “and I love showing visitors, especially children, what you can see out on the mudflats.”

In a nearby copse we find the rest of the volunteers hard at work clearing brambles. A habitat is being created to attract back Nightingales, which last bred here in 2018. Cheryl tells me she lives locally and has been volunteering weekly over autumn and winter, “Even in the cold and wet I’ve enjoyed the variety of work from shifting tern rafts to removing invasive plants.” Cheryl sees herself as a beginner birdwatcher but tells me she learns a lot from experts here.

“My favourite place on the reserve is Church Norton,” she shares, which is next on our itinerary.

From the Visitor Centre we drive what would be a 2-mile walk to Church Norton car park on the southern tip of Pagham Harbour, and I can see why Cheryl thinks this place is special. The tide’s coming in fast but there’s still some exposed shingle from which we have great views of a seal eating a fish.

A flock of Grey Plovers are resting on a nearby island, and the calls of Curlews float across the water. Gail tells me this is the spot in summer to watch breeding birds such as Sandwich, Common and Little Terns.

Afternoon magic

Back at the Visitor Centre I meet long-term RSPB member Tony who’s been birdwatching at Pagham Harbour for nearly 70 years, and I ask what changes he’s noticed over that time. “It’s great to see Avocets doing well here despite the urban development around the two nature reserves,” he tells me. Pagham Harbour and Medmerry nature reserves are almost the only remaining undeveloped areas left on this part of the Sussex coast.

After lunch, Roy, Gail and I drive just under 3 miles to Medmerry and make our way along the main track through the reserve. Roy points out the Stilt Pools where the Avocets should breed in the summer and where a pair of Black-winged Stilts bred in 2014.

Later, after the excitement of finding the Black Redstart, and with the sun sinking towards the Solent, my visit is drawing to an end. We’ve managed to squeeze both Pagham Harbour and Medmerry within a short winter’s day, but there’s more than enough to justify a longer visit to these two large reserves. I’ll definitely be coming again.

We’re walking back to the car when Gail points out a Barn Owl in front of us, quartering the fields outside of the flood bank. I watch, holding my breath, as this silent, luminous bird flies towards the shingle. Just for a moment, its pale feathers are lit up in vivid apricot shades against the orange and red sunset before it vanishes into the dusk. Magical.

Listen to this feature here:

Visitor guide: RSPB Medmerry and Pagham Habour, Chichester

Getting there

Bus 51 will drop you outside Pagham Harbour’s Visitor Centre. From here, walk the footpath for 1.8 miles to Medmerry. Bike Route 88 leads to Pagham Harbour’s Visitor Centre, and take the Medmerry Cycle Link from there. The nearest station is Chichester.

Entry

Free, with free parking for members.

Season highlights

In winter, the skies are filled with flocks of Dark-bellied Brent Geese and Golden Plovers. As spring arrives, take pleasure in watching smaller migrant birds arrive for the season, and nesting season is the prime time to see Pagham Harbour’s tern colony.

This season’s star species

Pagham Harbour: Wigeon • Brent Geese • Marsh Harrier

Accessibility

Parking: Car park at Pagham Harbour has two accessible spaces.

Wheelchairs: Pagham Harbour’s Discovery Trail has a wheelchair-friendly option, but this can get muddy in winter. At Medmerry, there is a path from Easton Lane car park to Easton Viewpoint.

Dogs: Welcome on the public footpaths and bridleways under close control.

More info

Visit a nature reserve

From marshes and heathland to estuaries and cliffs, there is a diverse network of nature reserves all over the UK. They’re a chance for focused conservation work and for you to connect with wildlife, take part in fantastic events and enjoy the great outdoors. As an RSPB member you can explore throughout the year and witness our wildlife spectacles throughout the seasons.

Lough Foyle is Northern Ireland’s second largest intertidal habitat. Photo: Andy Hay (rspb-images.com)

You might also like

Comment: The outstanding east coast of England

Experience winter