There’s no sign of the shoreline as I gaze across coastal marshes, rinsed of colour by a light, creeping mist. On this grey November morning, the distance between me and civilisation feels a lot more than two miles – but I’m far from alone, if you count the thousands of birds that arrive here each autumn.

Apart from the main road, the only sign of life is the birds. Lots of birds. Winging in the sort of quantities that suggest this seemingly featureless landscape must in fact be somewhere special. Skeins of Pink-footed Geese ‘wink-wink’ through the diffused morning light, then a Starling murmuration swirls past – for a moment, forming the shape of a whale.

Exhilarating clouds of Golden Plover and Knot also join the aerial ballet, as if choreographed, above their soggy stage.

Saving a corner for nature

Despite being flat and featureless, RSPB Marshside is an interesting site. It borders the southern banks of the Ribble Estuary, a major stopover for winter migrant birds and some interesting vagrants wandering across the Atlantic. And apparently, within living memory, most of it was underwater at high tide. I cross the main road to the visitor centre to find out more. Here, I meet Site Manager Alex Pigott.

The coast road zooms along an embankment bisecting the site, which now separates saltmarsh from freshwater marsh and pools. But things used to look very different. The housing estate visible inland stands on what was once tidal saltmarsh. Over centuries a series of sea walls were built, each reclaiming more land for farming or housing.

Alex tells me they built the road in the 1970s and drained the inner marsh. “Initially, the plan was to build on it; for about a year they tried pumping water off it. So this site could easily have become housing.”

I eye the bustling landscape dubiously. It looks as though it’s always been there with its huge, contented flocks. But some straight-cut drainage channels on the map betray human interference.

“Those are from when they tried to drain it,” Alex explains. She points at a lagoon in the middle distance. “Polly’s Pool there was once Polly’s Creek, a tidal inlet where local shrimpers and fishermen used to moor their boats and children used to swim.”

The RSPB arrived in 1994, leasing the site to improve it for the birds and people. The cattle remained though, creating a mosaic of habitat with low-density grazing, and depressions in the ground that Lapwings love to nest in.

Life flourishes here

From saltmarsh to farmland to rare coastal grazing marsh all in living memory, my mind is blown at how fast a landscape and its species can change. It’s both dynamic and timeless.

“We get plenty of bird enthusiasts here, along with our fair share of rarities,” Alex smiles. “Last month we had a Lesser Yellowlegs from North America, a Pectoral Sandpiper and our second Broad-billed Sandpiper. The serious birders will scan flocks of Wigeon and Teal looking for American Wigeon and American Teal among them, or the occasional Snow Goose; winter is an amazing time to see the variety.”

‘Some kids have never even seen the sea. Coming here can change their lives’

I can see plenty of variety standing right here in the visitor centre hide – no less than seven duck species, including Teal, Gadwall, Pintail and Shoveler, are dabbling away right under my nose amid flocks of Golden Plover, Starling and Lapwing. It’s a brilliant place for beginners to learn their waterbirds. Raptors, too – from the lookout across the road you can look for Hen and Marsh Harrier, Merlin and even owls.

Walking along the main road (perfect for bicycle birding), I can make out hundreds of grazing Pink-footed Geese, camouflaged against the terrain until they lift breathtakingly into the air.

“We also have rare plants such as Brackish Water-crowfoot,” says Alex. “Because of the site’s history as a saltmarsh, and tidal sediment creeping in under the road barrier, the water is brackish in parts.” And it’s all just one part of a wider landscape that’s one of the UK’s top wader hotspots.

“The Ribble is the most important single river estuary in the UK,” she continues. “It’s got big, open mudflats; sand ridges and beaches; saltmarsh and brackish lagoons, all close together. It attracts a quarter of a million birds every autumn, coming down from the Arctic tundra – Greenland, Siberia, Scandinavia and Iceland.”

This is why the Ribble Estuary National Nature Reserve is a Futurescape: a mosaic of highly protected sites managed by different landowners working together to create landscape-scale conservation. Marshside is one piece in this jigsaw. Just up the road, RSPB Hesketh Out Marsh is another.

Inspiring the next generation

There’s no reception building here – but there’s a reason for that. On the far bank of the estuary, I can make out the town of Lytham. Over there, on the waterfront, is the RSPB’s gateway visitor centre for the entire Ribble Estuary. I hop in the car and head over.

The RSPB Ribble Discovery Centre at Fairhaven Lake is housed in a funky, restored boatshed on the banks of a man-made lake along the estuary foreshore – a mix of sand dunes and mudflats.

It’s here that you get a sense of the whole wider landscape; how it connects and works for wildlife. Thanks to support from members, this place works hard to engage the local community in the ecosystems around them, which in turn helps protect nature for future generations. It starts with the kids.

Passion shines through Fairhaven’s Visitor Experience Officer Jo Taylor, a former teacher.

No worksheets or classrooms here; she takes school groups straight out onto the mudflats and gets them mucky, learning about the species that call it home.

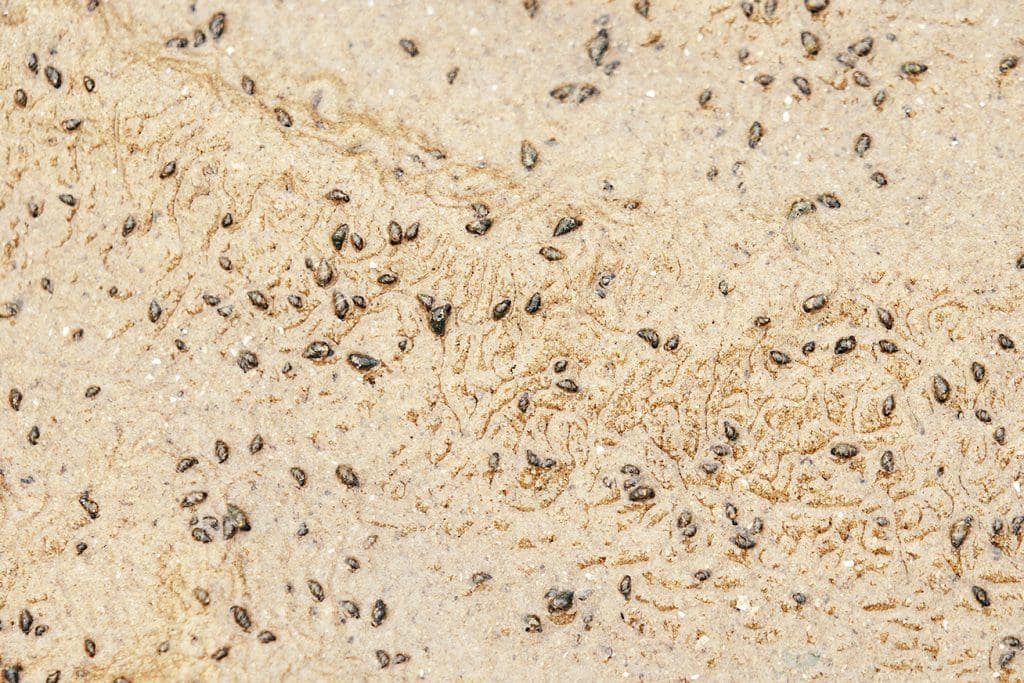

“Look at this,” she enthuses as we step from the sea wall onto the muddy sand.

I look down, but all I can see are… “tiny black stones?”

“Not stones,” Jo corrects me. “Hydrobia snails. This whole estuary is littered with them. The Shelducks love them. They scoff these snails in their millions.”

In disbelief, I scrape up a handful of sand and peer at it. I had no idea snails could be that small – tiny, perfect cones barely 2mm high.

“These mudflats are a giant buffet,” Jo explains. “Packed with Bivalve molluscs, Ragworms, Lugworms, Hydrobia – it’s a feast for Black-tailed Godwit, Dunlin, all wading birds. We take families mud-dipping here and pull out hidden invertebrates, identifying each one and its unique adaptation.

We talk about predator-prey relationships and how species sit in separate niches so they don’t outcompete.

“Some kids have never even seen the sea,” Jo adds. “Coming here can change their lives.”

I return to the bright, cosy centre, which sells everything from coffee to optics and showcases the local species. As I gaze back across the Ribble towards Marshside and Hesketh, I realise how important this landscape is for birds and how this centre sits at its heart, connecting landscape, species and people. I can see why the birds come, and I’m glad I came, too.

Visitor guide: RSPB Marshside, RSPB Hesketh Out Marsh, Fairhaven Lake visitor centre

Getting there

Marshside is 2.6 miles from Southport train station and served by the main road, National Cycle Network and the No 44 bus. Hesketh is one mile from the No 2 bus route from Preston to Southport. Fairhaven Lake is 50 metres from Andsell and Fairhaven station in Lytham St Annes.

Entry

Free for RSPB members.

Season Highlights

At dawn and dusk, huge winter flocks take to the air in a breathtaking display. On the water, look for occasional vagrants and rarities amid resident wildfowl and waders.

This season’s star species

• Lapwing • Black-tailed Godwit • Shelduck • Pink-footed Goose • Redshank • Wigeon

Accessibility

Parking: Marshside: free for Blue Badge holders and members; Hesketh: free parking, two Blue Badge spaces; Fairhaven: council car park, fees apply.

Wheelchairs: Marshside’s hides are wheelchair-accessible and several have seating. Hesketh has 500m of accessible trails, and benches at viewing areas. Fairhaven Lake has many smooth tarmac trails and step-free access.

Dogs: Must be kept on leads on trails.

From marshes and heathland to estuaries and cliffs, there is a diverse network of nature reserves all over the UK. They’re a chance for focused conservation work and for you to connect with wildlife, take part in fantastic events and enjoy the great outdoors. As an RSPB member you can explore throughout the year and witness our wildlife spectacles throughout the seasons.

Listen to this feature here:

You might also like

3 nature reserves to explore this autumn/winter

Your photos – autumn/winter 2023