Back when the RSPB’s Big Garden Birdwatch began in 1979, the Greenfinch was at number seven in the top 10 birds seen. In this year’s results, it’s at number 18. This reflects a broader loss across the UK. Numbers of these birds have been falling since around 2005, and there was a staggering 57% decline between 2012 and 2022.

In 2021, conservationists moved Greenfinches into the Red List category in the Birds of Conservation Concern report due to this severe decline. Chaffinch numbers have begun to decrease too, with 39% being lost between 2012 and 2022. For both species, the cause is a disease, trichomonosis.

What is trichomonosis?

Trichomonosis is caused by a microscopic protozoan parasite called Trichomonas gallinae. It typically infects the upper digestive tract of birds. Trichomonosis has been known to affect pigeons and doves, along with birds of prey, for many years. These bird species can be infected by different strains of the parasite, they can act as carriers or succumb to the disease.

Recently a strain of Trichomonas gallinae may have spilled over to finches, possibly at shared food or water sources, and has led to epidemic mortality across the UK and into mainland Europe.

Trichomonosis causes lesions along the gullet which interfere with the bird’s ability to swallow, causing it to regurgitate food and water. The parasite can spread between birds when they feed one another during courtship, or bring food to chicks, or through regurgitation at food or water sources.

A bird affected by trichomonosis typically shows non-specific signs of ill health, such as fluffed up plumage and lethargy, and may also have messy or wet feathers around the beak and shake its head as it tries to swallow.

In the right conditions, for example on moist food in mild weather, the parasite can survive outside of the bird host for a few days, however, it is killed by drying out and in most circumstances probably only survives a few hours outside a bird.

Trichomonosis does occasionally affect other species such as Blackbird, Robin and Dunnock, typically in gardens where finches are affected by the disease. It also affects other finches of conservation concern, such as the Bullfinch and the rare Hawfinch.

What’s being done?

Thanks to your support, the RSPB is collaborating with expert partners to find a solution. Becki Lawson is a wildlife veterinarian at the Institute of Zoology, which is the research division of the Zoological Society of London (ZSL). “We’ve been working with ornithologists at the RSPB and the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) to investigate the conditions that affect garden birds and their impact for at least 20 years,” she explains. “It’s been a team effort for a long time.”

‘Our goal is to understand endemic or ‘baseline’ diseases affecting garden wildlife, so that we’re able to identify new and emerging threats’

Just over 10 years ago, ZSL, working with Froglife, BTO and the RSPB, launched the Garden Wildlife Health project. The project covers the health of garden birds, amphibians, reptiles and Hedgehogs. Anyone who sees signs of ill health in their garden wildlife can report this through the project website (including uploading photos). Additionally, the BTO’s Garden BirdWatch participants provide systematic weekly data on bird numbers and health status throughout the year.

“Our goal is to understand endemic or ‘baseline’ diseases affecting garden wildlife,” Becki continues, “so that we’re able to identify new and emerging threats. We can then investigate the implications for wild animal welfare, biodiversity conservation, and perhaps public health or companion animal health.”

The Garden Wildlife Health team can then consider further surveillance and research and make recommendations for action. With the results of this research, the team can develop evidence-based best practice guidance for the public, decision makers and non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

“In the case of finch trichomonosis, we hope that we’ll be able to provide refined guidance for disease prevention and control, and also identify gaps in our understanding that we can work to fill,” says Becki.

What’s more, for the past year, with funding from Natural England (NE) through the RSPB-NE Action for Birds in England partnership, RSPB scientists have been working with BTO and ZSL to identify the most risky places for Trichomonas gallinae transmission in gardens.

“We’re visiting gardens where members of the public have reported suspected finch trichomonosis outbreaks either through the Garden Wildlife Health website, the RSPB Wildlife Enquiries team or directly after reading our science blog,” explains RSPB Conservation Scientist Will Kirby.

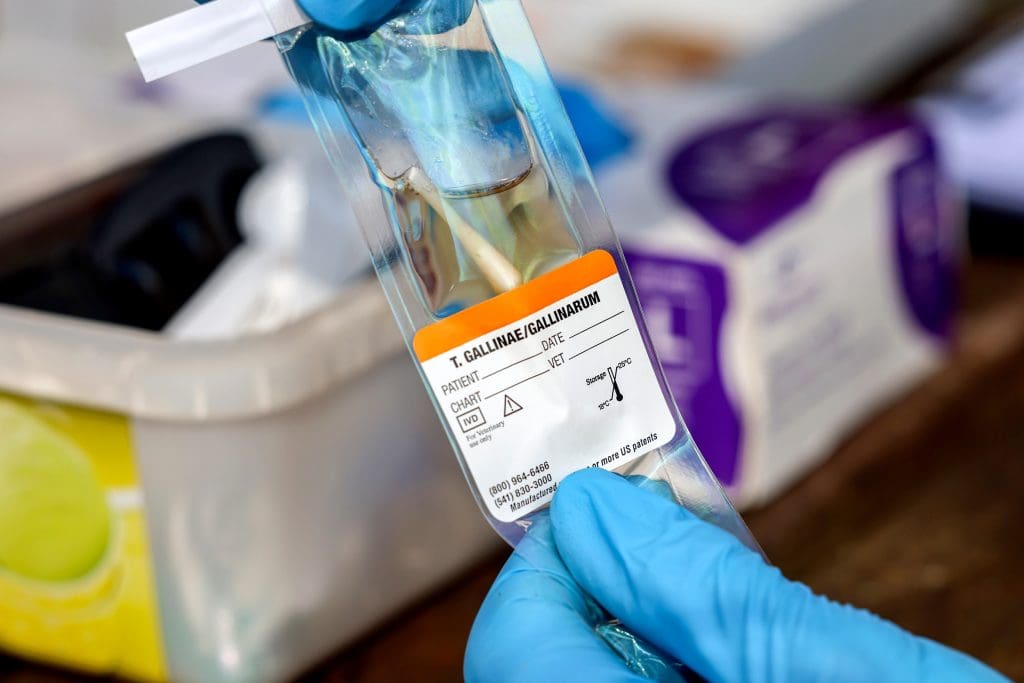

If the gardens prove to be suitable places for research, RSPB scientists visit and collect details of feeder and food types available to birds, as well as finding out how often the feeders are cleaned. They take swab and food samples from the feeders and from the ground below, along with water samples from bird baths and ponds. These samples are then inoculated into a specialist culture pouch and are kept at bird body temperature to encourage any parasites to multiply.

The samples are transferred to laboratories at ZSL where microbiologists check each day for signs of live parasites using a microscope. Pouches are later screened for trichomonas DNA which can confirm the species and strain.

One of the gardens in the study is owned by Anita and Mike Appleton. Anita says “It was very distressing to see sick birds in the garden. We saw sick Siskin, Brambling, Goldfinch and a Bullfinch.” Will and his assistant Alex set up cameras in the Appletons’ garden to capture the behaviour of birds before then returning to take samples on the following day. “It was very detailed,” Mike and Anita reported, “and we were grateful to be part of this important project.”

‘When we pull together, we’ve got a much greater chance of a better outcome’

Another aspect of this research has been led by Kate Plummer, BTO Senior Research Ecologist and her colleagues. They are investigating the role of elements such as weather, supplementary feeding (extra food put out by us) and local bird abundance as potential risk factors for finch trichomonosis outbreaks in gardens. Long-term citizen science data collected by participants in the BTO Garden BirdWatch project are used for this work.

“As individual organisations we might not be able to easily solve big challenges like this,” says Kate, “but when we pull together, we’ve got a much greater chance of a better outcome.”

What happens next

Kate, Becki and others are also supporting RSPB scientists in a wider review of the pros and possible cons of supplementary feeding in garden situations. The conclusions from this review will inform RSPB’s future position and advice on supplementary feeding and will be shared with members later in the year.

“As with many of the conservation problems we face, there are no easy answers,” says Katie-Jo Luxton, RSPB Executive Director, Global Conservation. “Feeding garden birds helps them survive during colder weather and periods where there is a shortage of wild food. But we have to weigh this against the risks of disease spread through garden feeding.”

Having close-up encounters with nature is important, too. Not only is it good for people’s wellbeing but it can also inspire them to do more to protect wildlife and wild places. In a biodiversity-depleted country where many are disconnected from nature, aiding that connection is more important than ever.

In December, RSPB shops suspended the sale of its bird tables, window feeders, seed catching trays and other items which have flat feeding surfaces. This is because, as an organisation, the RSPB aims to avoid risks when the impact is uncertain, and preliminary findings of the ongoing scientific review suggested they could present the highest risk due to the presence of regurgitated food and spoilage of food from faeces, feet and rain.

The RSPB is working with other Garden Wildlife Health partners to develop and test new designs for feeders that reduce the risk of disease spread. We will share the results and subsequent advice as soon as they are in. Updated guidance will be published in The RSPB Magazine, with our members amongst the first to know.

How you can help

The way we feed birds has changed over the years – we no longer use mesh bags of nuts. By working together we can make a difference.

• If you see signs of ill health in garden birds, you can help by reporting these observations to gardenwildlifehealth.org

• If you see sick birds, stop putting out food for two to four weeks. Then gradually reintroduce feeding but monitor the birds carefully. You may need to withdraw feeding for a further two to four weeks if you see more diseased birds, or three to six months if issues recur.

• The regular cleaning of bird feeders, at least weekly, can help slow or prevent the spread of various diseases.

Chaffinch. Photo: Ben Andrew (rspb-images.com)

You might also like

Secret lives of familiar garden birds

Big Garden Birdwatch results 2025