“A Barn Owl was out early, flying around hunting. As I watched it, I picked up the Short-eared Owl, way over in the distance. I started watching it through my scope. It was drifting towards where this guy was positioned in the heather. While I was watching it, the bird burst into a cloud of feathers. I knew what had happened. The guy on the moor had fired the shot.”

This account was given to the police by a local birdwatcher after they witnessed the illegal killing of a Short-eared Owl on a driven grouse moor in the Peak District in 2022. Though a gamekeeper was identified as the primary suspect, there was insufficient evidence to charge him. This is just one of hundreds of examples of bird of prey persecution in the UK today.

‘Birdcrime’ is the term we use for the illegal killing of birds of prey; it’s also referred to as raptor persecution. Methods used to kill birds of prey in the UK today are similar to those used in the Victorian times – the key difference is that, under the Wildlife and Countryside Act (1981), these acts are now illegal. Find out why protecting birds of prey has long been a priority for the RSPB.

‘The RSPB’s Birdcrime Report is the only long term data set of raptor persecution in the UK. Your support makes this work possible’

Shooting is the most common type of persecution incident. While some birds die instantly, many are left with severe injuries, unable to fly, leading to a slow and agonising death from starvation or exposure. Another common method used to illegally kill birds of prey is trapping. Criminals will misuse spring traps and crow cage traps and place them near feeding or nest sites to catch unsuspecting birds of prey. Footage gathered by the RSPB Investigations team has revealed that, in many cases, once trapped, these birds are then bludgeoned to death.

Criminals will also use poisons to kill birds of prey. Meat baits are laced with highly toxic and often banned pesticides and laid out in open areas of the countryside to purposefully attract scavenging and opportunistic birds of prey. Once exposed to these excessively high concentrations of dangerous poisons, death is typically swift but excruciating. This illegal and indiscriminate method poses a threat to wildlife, domestic animals and people.

The tip of the iceberg

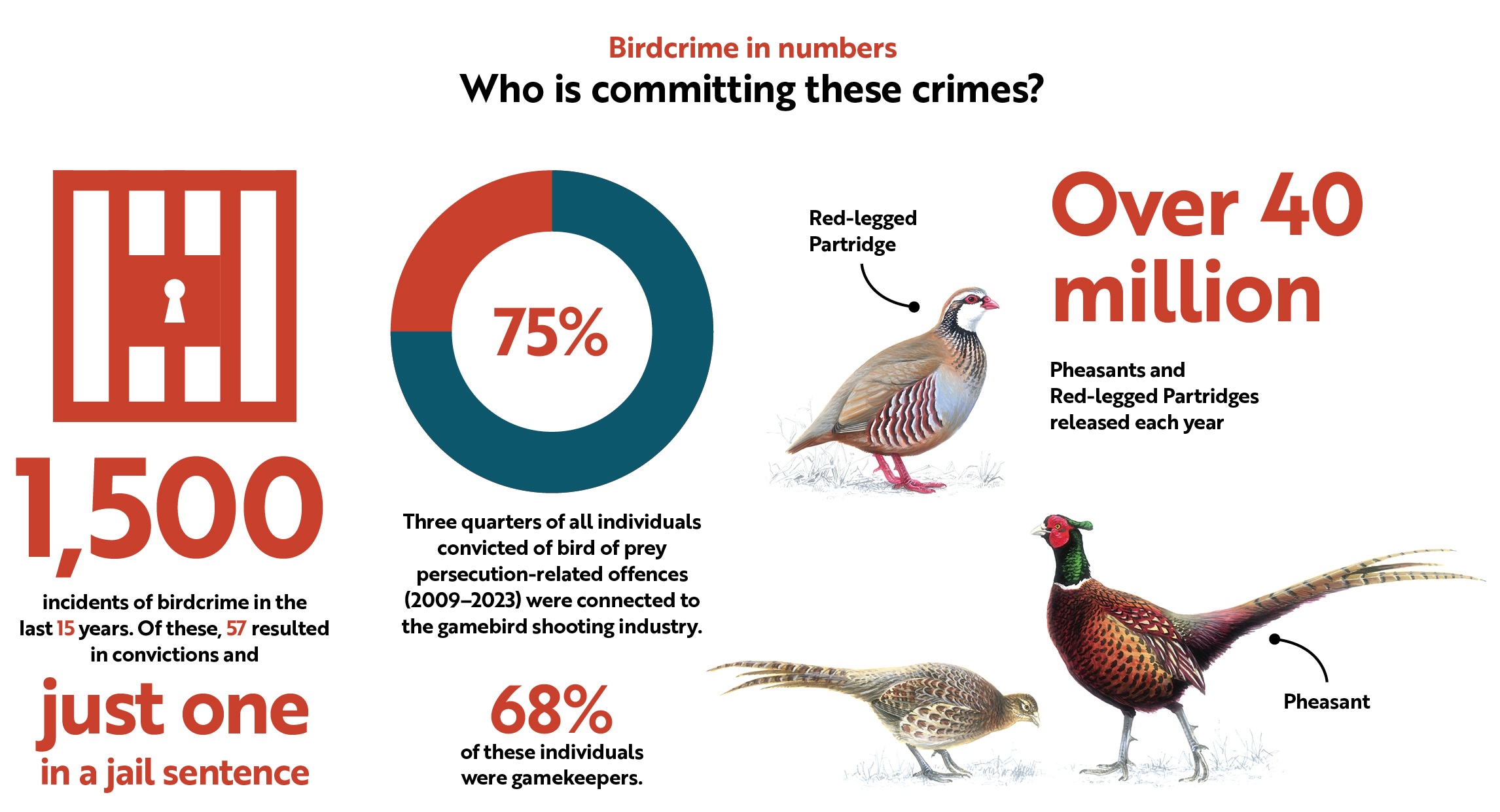

Statistically, many of these crimes are linked to the commercial gamebird shooting industry, which has grown substantially across the UK in recent decades. In upland areas, where profits rely on wild Red Grouse populations, there has been an intensification of habitat and predator management practices to boost grouse numbers for shooting. Meanwhile, lowland regions have witnessed a dramatic rise in the release of non-native gamebirds. To try to maximise gamebird numbers, some individuals are illegally killing birds of prey to remove any risk of predation and to increase profits.

Read more about how methods used for managing grouse moors affect birds of prey.

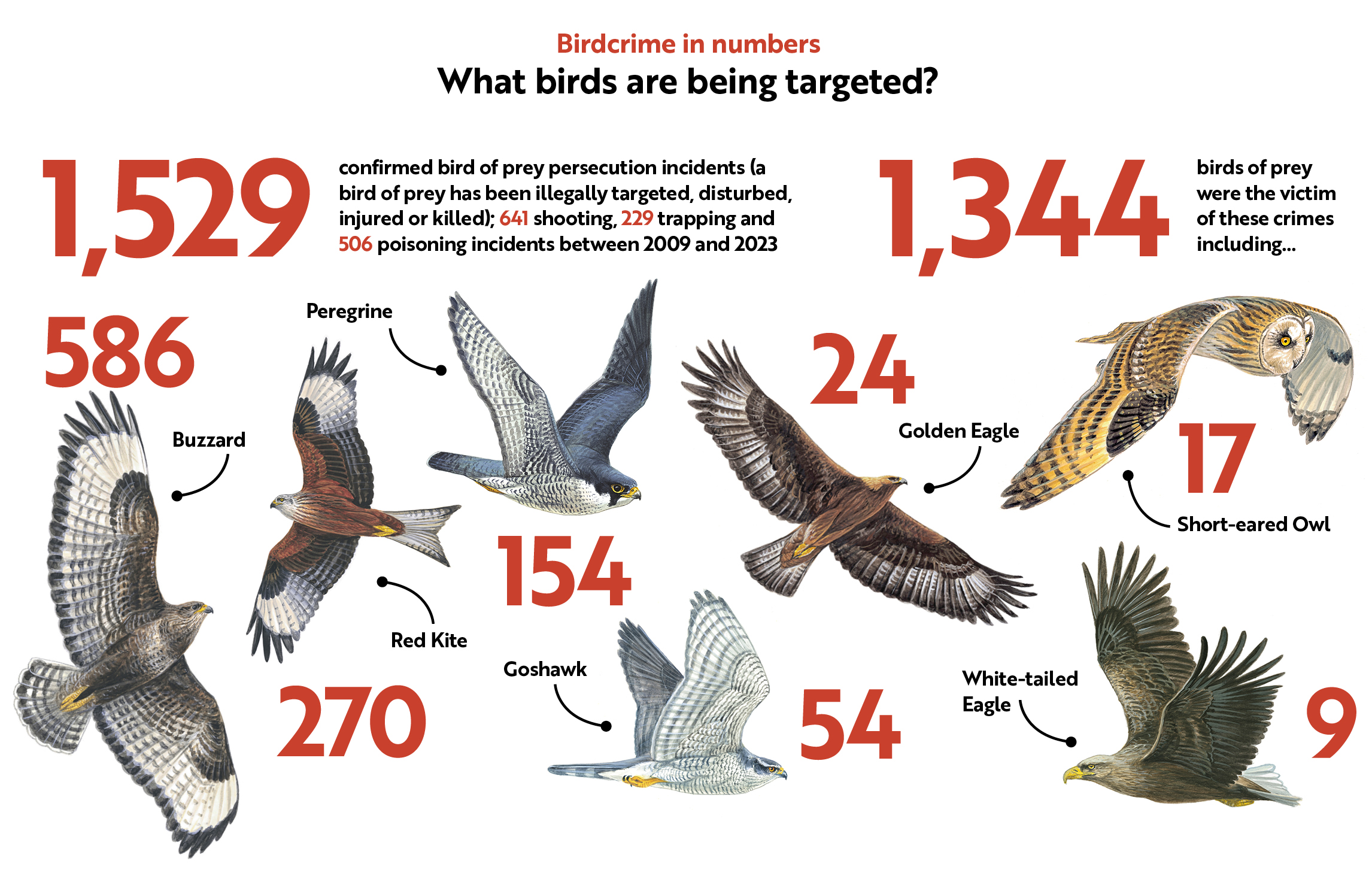

Although all birds of prey have been protected by law for over 60 years, the RSPB’s latest Birdcrime report reveals that there were over 1,500 confirmed incidents of bird of prey persecution between 2009 and 2023. All of these incidents were independently verified by postmortems, toxicology tests, forensic analyses or eyewitness accounts. This is a significant number, but this figure represents only a fraction of the true number of these crimes being committed. Many incidents take place in remote areas where they often go undetected and those committing these crimes go to great lengths to hide them.

Mark Thomas, UK Head of Investigations, adds: “With their iconic status and incredible agility, birds of prey seem almost invincible, but they don’t stand a chance against a shotgun, highly toxic pesticides or an illegal trap. Sadly, these magnificent birds are often an easy target for those with criminal intent. The law isn’t protecting them and we need something to change significantly, especially in England, to effectively stop the killing.”

Hen Harriers were almost driven to extinction in England in recent decades as a direct result of persecution. The intensity of illegal killing in upland areas has suppressed Hen Harrier breeding numbers far below their natural population level in England, where there is enough suitable habitat to support over 300 pairs but only 50 territorial pairs were recorded in 2023.

The changing face of birdcrime

Iolo Williams worked for the RSPB Investigations team from 1985 to 1998. He shares what it was like working on the team then, what he thinks of the issue now and how we can bring about an end to this persecution.

“[In the beginning], there were no drones, no cameras. It was just bums on the ground. We got volunteers to guard Red Kite nests, because egg collecting was a huge issue. If we managed to fine someone, we were delighted because that was a huge result. Eventually we managed to get the army in and then things died down a bit because word got around. There’s less poisoning now because I think the landowners and the keepers know that, if they put out bait with poison on it, there’s an increased risk of being caught, whereas if they go out in the night with thermal sights on their rifles they can shoot whatever they like. It hasn’t got any better; it’s just shifted, in Wales anyway. I suppose the solution is to change those people that are making their livelihoods from grouse shooting and pheasant keeping. And the law needs to change as well, and it needs to be applied properly and these crimes need to be taken seriously. I’m a massive admirer of the RSPB Investigations team and the work that they do.”

Iolo went out to Italy in 1997 to help the LIPU confiscate homemade bow traps used to catch Robins in the hills above Parma. Photo: Iolo Williams

Listen to the full interview of presenter and former Birdcrime Investigator Iolo Williams with The RSPB Magazine Editor Emma Pocklington:

Since 2014, the RSPB and other organisations have been monitoring Hen Harrier movements and survival using satellite tags. Data from these devices have revealed a catalogue of persecution incidents which would otherwise have gone undetected. This has informed scientific studies, revealing the devastating impact that these crimes are having on the conservation status of this species.

Boots on the ground

Conservation initiatives, reintroduction programmes and legal protection have helped some bird of prey species in the UK recover from historic persecution. White-tailed Eagles fly free in parts of Scotland and southern England, Red Kites have spectacularly bounced back from extinction and Golden Eagles are now making a comeback in Southern Scotland. Despite these incredible conservation successes, the continued persecution of bird of prey species is still hampering many conservation efforts.

For over 30 years, the RSPB Investigations team has been detecting and recording these crimes, assisting with police investigations and working tirelessly to put an end to raptor persecution.

Now 15 strong and working across the UK, the team continues to shine a light on these crimes, exposing the true scale of this issue. The Investigations team spend hours in the field in cold, wet, challenging conditions to detect these crimes.

“Fieldwork can be incredibly challenging when working long hours, walking over difficult terrain and in all weathers for little reward, but it’s the sense of camaraderie and belief within the team that pushes you on,” says Howard Jones, Senior Investigations Officer.

Investigations Officer Niall Owen adds: “Being on the front line, combating raptor persecution, is a rewarding, tough but often demoralising business. Dealing with illegally killed birds of prey on a regular basis takes its toll, but knowing you’re out there to protect birds is an unrivalled sensation.”

Through intelligence gathering and fieldwork, the team has detected and reported hundreds of bird of prey persecution incidents, assisted in police-led investigations and supported the work of the National Wildlife Crime Unit.

‘Hen Harriers were almost driven to extinction in England as a direct result of persecution’

Although some incidents result in successful prosecutions, without strong evidence to link an individual to the crime, most cases are unresolved. The culprit goes unpunished, free to offend again.

Change is in the air

In 2024, Scotland’s Parliament took huge steps to effectively challenge the illegal killing of birds of prey by introducing the licensing of grouse shooting under the Wildlife Management and Muirburn (Scotland) Act. Now, if evidence shows that a raptor persecution incident is linked to the management of a licensed area, a shoot’s licence can be revoked, creating a significant deterrent to wildlife criminals.

This is groundbreaking legislation, and the RSPB is now calling for the licensing of all gamebird shoots by Governments across the UK. This will help put an end to the scourge of bird of prey persecution linked to this industry.

“We hope similar positive steps will soon be seen in England, where relentless persecution has left some upland areas devoid of bird of prey species,” says Ian Thomson, the RSPB’s Investigations Manager. “Current laws need to change, but with our members’ support, we have and will continue to make a difference for birds of prey. Now is the time for the killing to stop.”

How you can help

Spread the word: Learn more about bird of prey persecution by reading the latest Birdcrime report. The RSPB creates the only long-term data set of raptor persecution in the UK. The team updates these figures every year. Read more about Birdcrime.

Report crimes: We rely heavily on the support of the public to help us detect and prevent crimes against birds of prey. You are our eyes and ears on the ground, and we need your help more than ever to put a stop to the illegal killing of these birds. To learn more about how to report crimes against birds of prey, click the link below.

RSPB Investigations Officer Jack Ashton-Booth undertaking fieldwork in The Forest of Bowland. Photo: Anastasia Taylor-Lind, (rspb-image.com)

You might also like

Raptors still being illegally persecuted across the UK

Three questions: RSPB Investigations’ Howard Jones on threats to birds of prey