The skies may be grey but ducks look their best in winter

The winter months may mean shorter days and lower temperatures but for many birds, our lakes, seas and wetlands provide refuge from harsher conditions further north.

Thanks to the support that you give as an RSPB member, our nature reserves host large numbers of ducks along with other wildfowl (geese and swans) and waders in winter. For example, in February 2024 RSPB nature reserves supported around 480,000 waterbirds. These included ducks such as Gadwall, Pintail, Shelduck, Shoveler and Wigeon, for which RSPB nature reserves provide food and habitat for more than 10% of their British wintering population.

Some ducks are dabblers, feeding on the surface of the water, and others are divers, plunging underwater to find their food.

Here’s your guide to those wonderful winter ducks, sorted by the habitats you may find them in.

Jump to species: Gadwall, Goldeneye, Goosander, Mallard, Pintail, Pochard, Red-breasted Merganser, Scaup, Shelduck, Shoveler, Smew, Teal, Tufted Duck, Wigeon, Common Scoter, Eider, Long-tailed Duck, Velvet Scoter

Lakes, ponds and rivers

Gadwall

This dabbling duck looks grey but a closer peek reveals intricate speckling on its breast and wings. Males have a distinctive black rear, visible when they ‘upend’ in search of food. Females resemble Mallards but are more pale with a clean white wing patch.

They feed on plant matter, particularly stems, leaves and seeds. Gadwalls prefer shallow waters but can’t always reach down far enough to get at the tasty underwater foliage. To avoid missing out, they often follow Coots, snatching leaves from their beaks after they surface from diving!

Gadwalls nest in low numbers here; however, winter sees an influx join us from other parts of Europe, increasing numbers to around 31,000.

Female (left) and male (right) Gadwall. Photo: Ben Andrew (rspb-images.com)

Male and female Gadwalls foraging in water and reeds for food. Video: RSPB (rspb-images.com)

Goldeneye

This handsome diving duck is recognisable by its unusual buffalo-shaped head and yellow (golden!) eyes. Males have a white patch near the bill and iridescent green heads, while females have chocolate brown heads, contrasting with their grey bodies. During courtship displays (which you may see here in winter), the male dramatically throws his head back so that it rests on his back.

Goldeneyes prefer deep water, so you will most likely see them in larger lakes and reservoirs. Though Red-Listed in the UK, conservation efforts in Scotland have increased breeding pairs to 200 using specially designed nestboxes. In winter, over 20,000 arrive from northern Europe.

Goosander

Members of the ‘sawbill’ family, these ducks have serrated bills, allowing them to catch fish. Males are white with glossy green heads, black wings and vibrant red bills. Females are grey with white throats and gingery-orange heads.

Initially breeding in the UK in 1871, Goosanders nest in holes along the riverbank. These ducks were first established in Scotland, and their numbers have continued to grow with year-round sightings in Wales, north and west England and, more recently, the southwest.

In winter there are many more Goosanders here, with numbers swelling to 14,500. Look out for them in freshwater wetlands and rivers.

Adult male Goosander. Photo: Ben Andrew (rspb-images.com)

Adult female Goosander. Photo: Ben Andrew (rspb-images.com)

Mallard

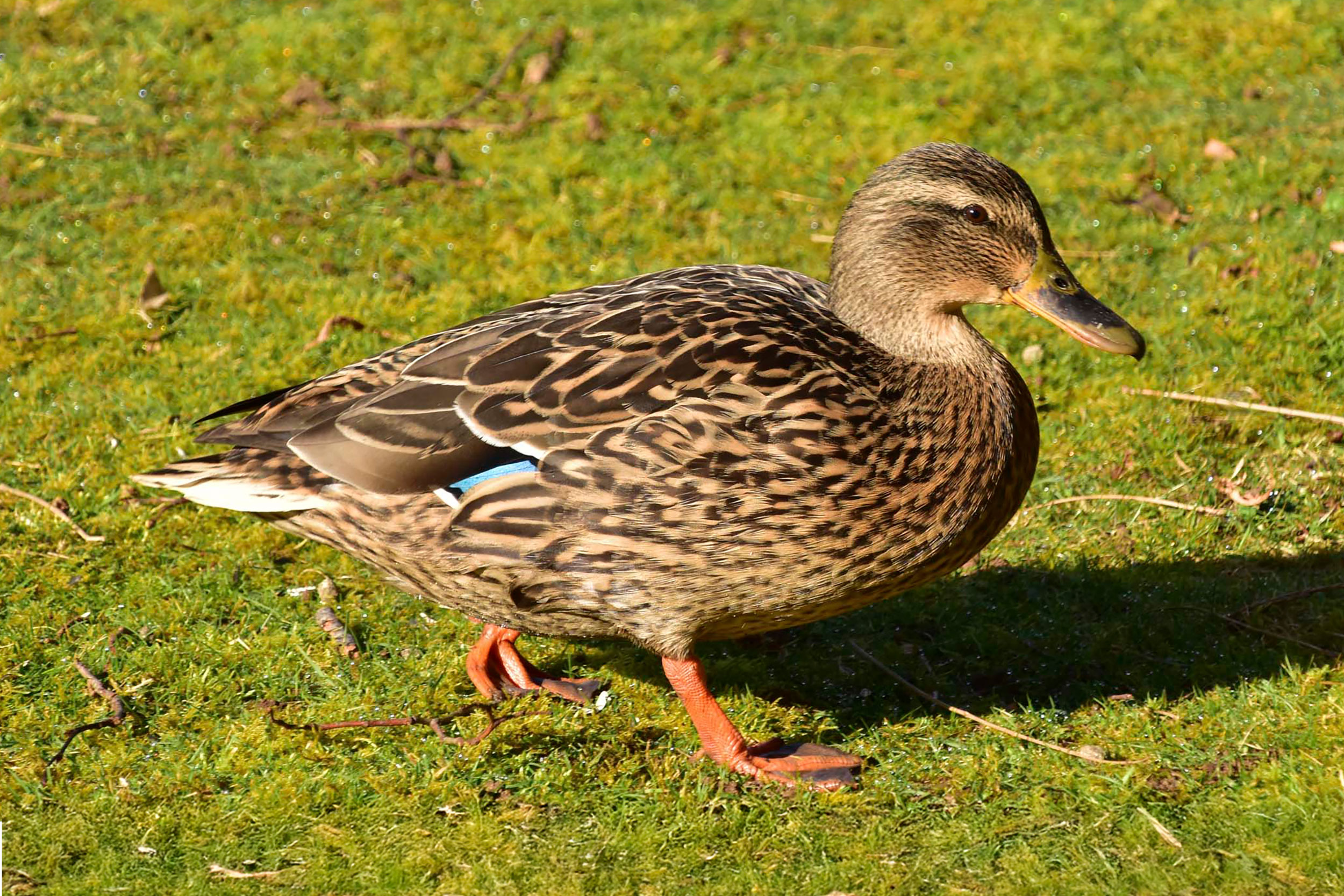

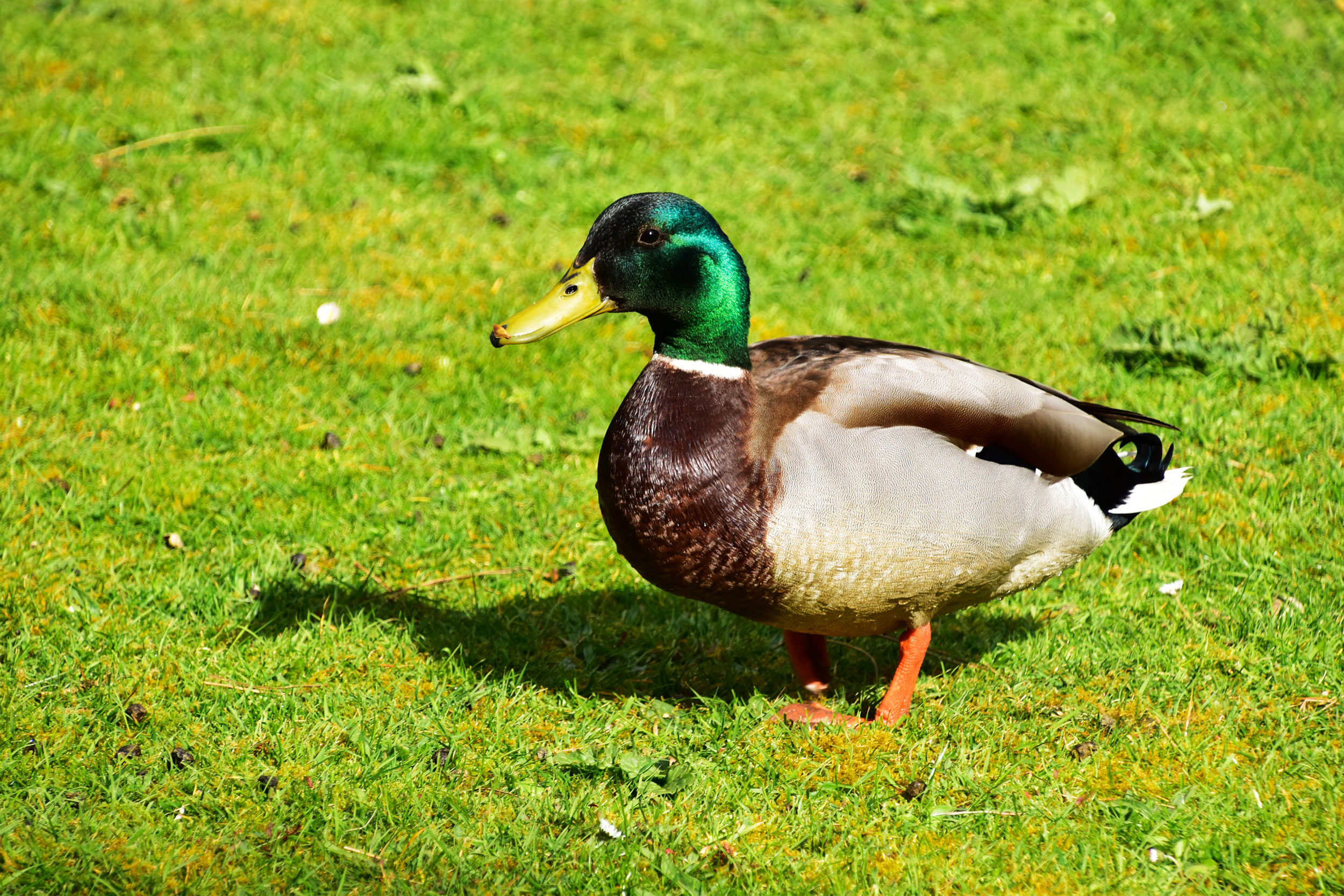

The distinctive male Mallard has a green head, yellow bill, maroon-brown chest and grey body. Females are mottled brown and look so different that it was originally believed they were a different species!

The much-loved Mallard is a common sight at our local parks and ponds – you may remember feeding them as a child. However, we now know there are far better things to feed them than bread! Their diet consists of berries, insects, seeds, shellfish and plants, so if you want to feed them in your local pond, sweetcorn, oats, shredded lettuce and peas will all be received with enthusiasm. Around 675,000 Mallards are here in winter.

Female Mallard, RSPB The Lodge. Photo: Robert Simmons (rspb-images.com)

Male Mallard, RSPB The Lodge. Photo: Robert Simmons (rspb-images.com)

Pintail

This elegant duck is named after its long, pointed tail feathers. Males have chocolate-coloured heads, long creamy necks and grey bodies, whereas females are mottled brown with just a hint of a longer tail and a long neck. Look out for their curved back, pointed wings and long tail in flight.

These birds are dabblers, feeding on plants and invertebrates. While a small number breed in the UK, winter brings 20,000 of them to our coasts and estuaries. The record for the longest non-stop recorded journey taken by a Pintail is 1,800 miles! Migration routes can cross many countries, which is why the RSPB is working with partners such as BirdLife International, advocating for both local and global strategies to protect our wildlife.

Pintail pair swimming – the female is on the left. Photo: Ben Hall (rspb-images.com)

Adult male and female Pintails swimming among Pochards, UK. Video: RSPB (rspb-images.com)

Pochard

This diving duck is found in lakes and reservoirs, feeding on waterweed and small invertebrates. Male Pochards are striking birds, with chestnut brown heads, black breasts and grey bodies. Females are a darker grey-brown.

Interestingly, females migrate further south than males so the flocks in UK nature reserves often consist mostly of males. Winter populations reach 29,000 pairs but, sadly, declining numbers have put them on the UK Red List. Pressures vary, but algae blooms in particular, caused by agricultural runoff, make it harder for them to dive for food. We’re focusing on wetland habitat restoration, ensuring that there are plenty of places for Pochards to feed and shelter during winter.

Male Pochard swimming. Photo: Ben Hall (rspb-images.com)

Female Pochard swimming. Photo: Ben Hall (rspb-images.com)

Red-breasted Merganser

Another ‘sawbill’ diving duck, the Red-breasted Merganser eats fish and lives in both freshwater and saltwater. Many move to the coast in winter when their numbers increase to around 11,000.

They look similar to Goosanders, although the males have a black, white and grey body with a red breast and a green tufted head. Females are more difficult to tell apart as they are grey in both species, but Red-breasted Merganisers’ head colour fades gradually, which is unlike the Goosander’s sharp neck contrast. When identifying between them, note that the merganser’s beak curl is less pronounced than a Goosander.

Female Red-breasted Merganser swimming. Photo: Ben Andrew (rspb-images.com)

Male Red-breasted Merganser. Photo: Nick Greaves (Shutterstock.com)

Scaup

These diving ducks resemble Tufted Ducks but lack the tuft and have larger heads and a more rounded shape, more like a Pochard in their size and outline. The drakes have a lovely silvery back, contrasting with the white flanks and bottle green heads. The brown females have a striking, large patch of white at the base of their beaks.

They are our rarest breeding duck and Red-Listed, with only a handful breeding here annually. In winter, around 6,400 Scaups gather along the coastline and in large, deep lakes and reservoirs, boosted by arrivals from the north. The RSPB is collaborating with partners such as the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust and The National Trust to seek UNESCO World Heritage status for key coastal wetlands on England’s East Coast, protecting wintering habitats for migratory birds.

Male Scaup. Photo: Erni (Shutterstock.com)

Female Scaup. Photo: F Demonsant (Shutterstock.com)

Shelduck

This big, colourful bird sits in a class of its own, and is larger than a Mallard but smaller than a goose. It is mostly white with a green head and neck, red bill and chestnut belly stripe. The male Shelduck has a more prominent knob at the base of the bill, and the female has a slightly narrower chestnut stripe.

Shelducks nest underground, often in rabbit burrows, and are found across the UK in coastal marshes and muddy estuaries. They feed on invertebrates hidden beneath the sand and silt, with around 51,000 of them overwintering in the UK.

Adult male Shelduck. Photo: Ben Hall (rspb-images.com)

Adult Shelducks. Video: RSPB (rspb-images.com)

Shoveler

Named for their easily recognisable spade-like bills, Shovelers feed by sweeping their large flat bills through the water, filtering out invertebrates, seeds and plant matter. Males have dark green heads, chestnut breasts and rusted orange flanks. The females are mottled brown and among the easiest female ducks to identify as they have the same spade-like bill.

Shovelers can be found nesting in small numbers in southern and eastern England and also in Scotland. In winter, local birds move south, replaced by an influx of arrivals from northern Europe, increasing numbers to around 19,500. Look for them on shallow freshwater lakes and marshes.

Shovelers swimming and feeding. Video: RSPB (rspb-images.com)

Smew

Another diving duck in the ‘sawbill’ family, the male Smew is easy to identify, with a snow-white body and black mask and back. Their plumage has given them the nickname ‘white nuns’, as they look like they’re wearing white hoods. Females are grey with red heads.

These dainty Red-Listed birds are in decline, and much scarcer here. Rising global temperatures mean fewer species need to make the journey across the North Sea to avoid freezing conditions, a phenomenon known as ‘short-stopping’.

Female Smew swimming. Photo: Ben Hall (rspb-images.com)

Male Smew. Photo: F Demonsant (Shutterstock.com)

Teal

Our smallest duck can be found dabbling in wetlands across the UK. Males have speckled grey bodies, chestnut heads with green eye patches, and yellow and black tails. Females are mottled brown and both sexes display green wing patches (speculum) in flight.

A small number breed in Scotland but numbers swell to around 210,000 in winter when visitors arrive in the south and west of England. Groups of Teals are called “springs” because they take off rapidly, almost as if they have jumped into the air!

Male Teal. Photo: Andy Hay (rspb-images.com)

Female Teal. Photo: Alex Cooper Photography (Shutterstock.com)

Tufted Duck

Known for the males’ characteristic tuft, these fancy diving ducks are a common sight in lakes and ponds across the UK. They eat plant matter, molluscs and insects, so if you’re visiting them at your local duck pond it is best to feed them vegetable scraps and uncooked oats rather than bread.

Males have black heads and tufty black crests, as well as necks, chests and backs with white flanks, while females are mainly chocolate brown. Both sexes have bright yellow eyes. We have Tufted Ducks year-round here, but they are joined by winter visitors from Iceland and northern Europe, bringing numbers to around 140,000 birds.

Adult male Tufted Duck. Photo: Ben Andrew (rspb-images.com)

Adult female Tufted Duck. Photo: Ben Hall (rspb-images.com)

Wigeon

Wigeons are pretty ducks which unusually spend much of their time on land, nibbling on short grass in their tight flocks. Males have chestnut heads, yellow foreheads, pink chests and grey bodies. Females are plainer, resembling Mallards but with pointed tails.

Winter brings around 450,000 Wigeons to the UK as visitors from Scandinavia, Iceland and Russia join our resident birds. Listen for their calls: they whistle instead of quacking! Wigeons will sometimes mate with other species of duck, producing hybrid young.

Adult male Wigeon. Photo: Ben Andrew (rspb-images.com)

Adult female Wigeon, RSPB Frampton Marsh. Photo: Ben Andrew (rspb-images.com)

Sea ducks

Common Scoter

The male Common Scoter is our only all-black sea duck, with a small yellow blob on its bill. Females are greyer with striking, paler cheeks. Winter numbers swell to 135,000 birds but you’ll likely need a telescope to see them well. These squat sea ducks are excellent divers, plunging up to 30 metres to hunt.

Common Scoters have small breeding populations in Scotland and Ireland but numbers have declined, placing them on the UK Red List. They feed on molluscs far out to sea, gathering in ‘rafts’ or long lines around our coast.

Male and female Common Scoters bobbing in rough water, RSPB Forsinard Flows. Video: RSPB (rspb-images.com)

Eider

The UK’s heaviest and fastest flying duck, the Eider spends its life on or around the sea. Eiders are easier to spot than other sea ducks, often venturing into harbours in search of shellfish. They have a short neck, large body and head with a long, wedge-shaped bill. Female and juveniles are mottled brown with dark barring but have the distinct long forehead with a grey bill. Young males are a mix of black and white. Adult males are white with a black crown, flanks, belly and tail. Their breast is a slight tint of pink with a lime green head.

Eider has long been associated with bedding: their soft downy feathers have been used to stuff quilts and pillows, nearly wiping out the population in the 19th century.

While renewable energy is an important part of our climate strategy, we must manage the impact on our seabirds. Offshore wind farms and tidal barrages can displace Eiders and other sea ducks from preferred foraging areas, so we are working at the higher policy level to ensure development prioritises the avoidance of highly sensitive bird areas at sea. Around 86,000 Eiders winter here.

Adult female Eider. Photo: Ben Andrew (rspb-images.com)

Adult male Eider displaying. Photo: Ben Andrew (rspb-images.com)

Adult male and female Eiders calling and diving for food. Video: RSPB (rspb-images.com)

Long-tailed Duck

This sleek sea duck does not breed in the UK but visits us during winter when around 13,500 of them arrive on our northern and eastern coasts. They are Red-Listed and vulnerable to oil pollution so it’s really important we protect their wintering sites.

Known for their striking elongated tail feathers, this is the most obvious identifying feature on the males, although females have a much shorter tail. Male Long-tailed Ducks are white with black markings and a pink and black bill. Females are brown and white, with no pink patch on their bill. Their diet includes a mix of cockles, clams, mussels and small fish and they will dive as deep as 60 metres to find the perfect snack!

Female Long-tailed Duck. Photo: Paul Reeves Photography (Shutterstock.com)

Male Long-Tailed Duck at RSPB Snettisham. Photo: Ben Andrew (rspb-images.com)

Velvet Scoter

These black sea ducks have thick necks, long bills, pointed tails and white facial markings. The drake is one of our most beautiful ducks – jet black with a white fleck behind its eye and an orange and black bill. The female is browner with white patches on her face. The trick to finding this species among the large rafts of Common Scoter is to look for the large white wing patches that both sexes show in flight and occasionally can be seen at rest.

They don’t breed in the UK, but around 3,350 birds visit our eastern coastlines in winter, especially in Scotland, Norfolk and north-east England.

Velvet Scoters are on the UK Red List and face threats from oil spills and depleted fish stocks. They are also protected by Schedule 1 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, so it’s an offence to disturb them.

Male Velvet Scoter. Photo: Oliver Smart (rspb-images.com)

Female Velvet Scoter. Photo: Bouke Atema (rspb-images.com)

Whether diving or dabbling, our resident ducks and wintering visitors bring a burst of beauty to our natural landscapes, and they remind us of nature’s seasonal rhythms. So make the most of them this season and see which you can find on your nearest RSPB nature reserve.

If you’d like to find out more about duck populations in the UK, take a look at the results of the WeBS (the Wetland Bird Survey). WeBS is a partnership between the BTO (British Trust for Ornithology), the RSPB, and the JNCC (Joint Nature Conservation Committee), and the survey is carried out by nearly 4,000 volunteers. See the results: Waterbirds in the UK

Learn even more about the UK’s ducks in this webinar, led by Jamie Wyver with RSPB expert Jon Carter.

Discover more about ducks in our Winter Ducks webinar recording

You might also like

A season woven with wonder

How we’re saving island species